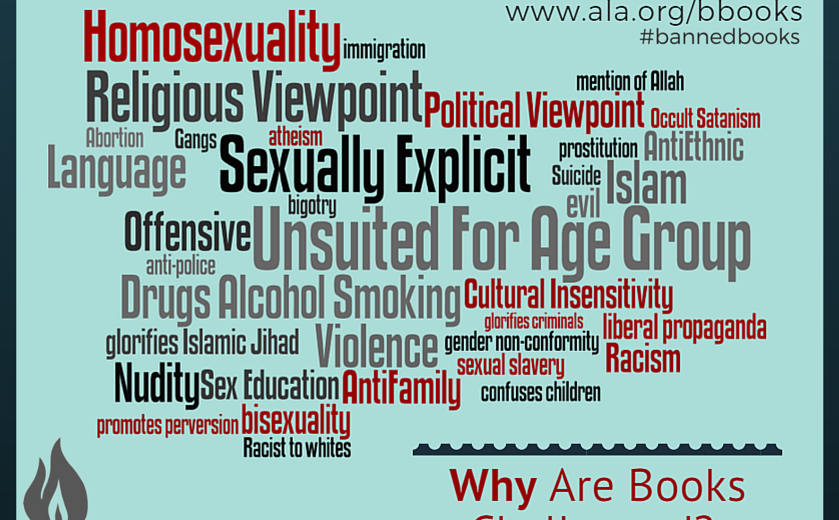

Since it’s Banned Books week, I found myself thinking about how sex is often the reason for censorship. Some books have been banned due to political subversion, questioning religion or disturbing violence but when you look at the list of reasons explicit sexuality comes up often. I decided to look into books banned for sexual themes to see what I could find. I found a long sex education books and novels people have been trying to censor from days gone by and even to this day. Some books are banned as soon as they are written; others only in specific countries and others were denied shipment by the US postal service due to the Comstock law. Some books didn’t get completely banned but challenged, which according to the American Library Association is a formal complaint to remove a book from a school or library.

Books about sex education were often banned for obscenity even though they were trying to educate and provide people with a more satisfying sex life. Marie Stopes wrote several books that were a hit with early 20th century housewives but the U. S. Customs Service felt was obscene enough to ban. The book “Married Love” was published in 1918 then banned in the U.S. until 1931. “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male” by Alfred Kinsey, published in 1948, was often censored or banned from bookshelves because of it’s content. The public was shocked by Kinsey’s survey of men and women’s sex lives.

One often hears “promoting homosexuality and perversion” as a reason to ban a book. The book “Our Bodies, Ourselves,” published in 1971 by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, was challenged for ten years. Their recommendation to take a mirror and explore your vulva was a bit too much for some people, as was their open discussion of abortion and homosexuality. Alex Comfort’s “The Joy of Sex,” published in 1972, was challenged at times but “The Joy of Gay Sex” by Charles Silverstein was banned because it was a graphic how-to guide for, well, gay sex.

Sex education for kids remains difficult to keep on the shelves even today. “It’s Perfectly Normal” and “It’s So Amazing” by Robie Harris have been on a list of the ten most frequently challenged books nearly since it was released in 1994. “It’s Perfectly Normal” made it to number one on that list in 2005. Some parents had a problem with the “clothing optional” and in flagrante delicto characters of the book. Too much nudity and sex in a sex education book, even though it’s in a cute cartoon style. Naked cartoon characters and upfront description of sex also made people uncomfortable in the book “My Mom’s Having a Baby” by Dori Hillestad Butler.

Some books deal with censorship for centuries after they’re written. “The Decameron” was written in the mid-1300s by Giovanni Boccaccio and was burned and banned in Italy in 1497 and 1553. The book is about seven women and three men telling stories while hiding from the Black Death outside of Florence. They each tell a story every day for ten days. Some of the 100 stories have quite sexually explicit themes. Surprisingly, it would be banned in the US at the start of the Comstock Law in 1873, confiscated in Cincinnati in 1922, banned in Boston in 1933 and appeared on the National Organization of Decent Literature’s blacklist in 1954.

There is an extensive list of popular books banned for explicit sexuality. “Moll Flanders” by Daniel Defoe was published in 1722 and fell victim to the Comstock Law in 1873. “Fanny Hill” by John Cleland was published in 1748 and banned in 1821. It was the last book banned in the US when it was banned again in 1963. Marquise De Sade’s “Justine” (known by its original title “Les Infortunes de la Vertu”) was the first novel written by De Sade in 1791 and the first of his to be banned.

Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” a collection of poems published in 1855, cost Whitman his job in 1865. The book was informally banned, and most libraries refused to buy it. It was banned in Boston in the 1880’s. James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” published in 1922, was banned until the court case United States vs. One Book Called Ulysses in 1933. “Lady Chatterley ‘s Lover” published in 1928 by D.H. Lawrence was banned until it had its own court case in 1959. “Tropic of Cancer” by Henry Miller was published in 1934 then banned soon after its release. “Lolita” by Vladimir Nabokov in 1955, “Naked Lunch” by William Burroughs in 1959, and “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg in 1956 were all banned because of sexual content.

We still have novels challenged due to their open discussion of sexuality. Books I remember from my youth like “Forever” by Judy Blume (which I read in Junior High along with “Wifey”) and “The Chocolate War” by Robert Cormier (which I remember reading in high school) to current books like “Drama” by Raina Telgemeier (which my daughter read and loved). It seems that every new sex education book that tries to give kids the information they need in a straightforward way is on the fast track to the banned list as soon as it’s released. Thankfully, Banned Books Week by the American Library Association has been reminding us since 1982 that preventing people from reading books to due controversial content is something we need to continue to fight against. We all need to celebrate the freedom to read.

Want to learn more about Banned Books? Check out Banned Books: Challenging Our Freedom to Read, available on amazon, through the link below. While you’re there, pick up some of the banned books you haven’t read yet and help Sexual History Tour. Disclosure: this is an affiliate link.