I did lots of driving over winter break, often 5-10 hours at a time. In that time, I had the radio on so I listened to lots of ads.

Lots and lots of ads.

In between the car dealership and fast food ads I kept hearing a weight loss ad that guaranteed a flat belly and would empty your gut of tons of toxic sludge. After hearing it a few hundred times, my brain started analyzing what I was hearing; you can’t physically have “tons” of undigested food in your belly, especially not toxic sludge, and someone couldn’t be so bloated it looks like belly fat. Is this legit? If not, why are they allowed to advertise? My brain started thinking about truth in advertising. Then I decided to write a post about one piece of historical non-truth in advertising that rolled around in my head on the drive back, Lysol’s use as a douche.

Let that roll around in your brain for a bit. Lysol. Douche.

A while ago I had stumbled upon old ads for Lysol as an effective douche, its cleansing power capable of saving marriages. I went back into the history of Lysol to figure out how this came about and found another horrifying bit of Lysol trivia. It was also used as birth control.

Now let that thought sink in. Lysol. Birth. Control.

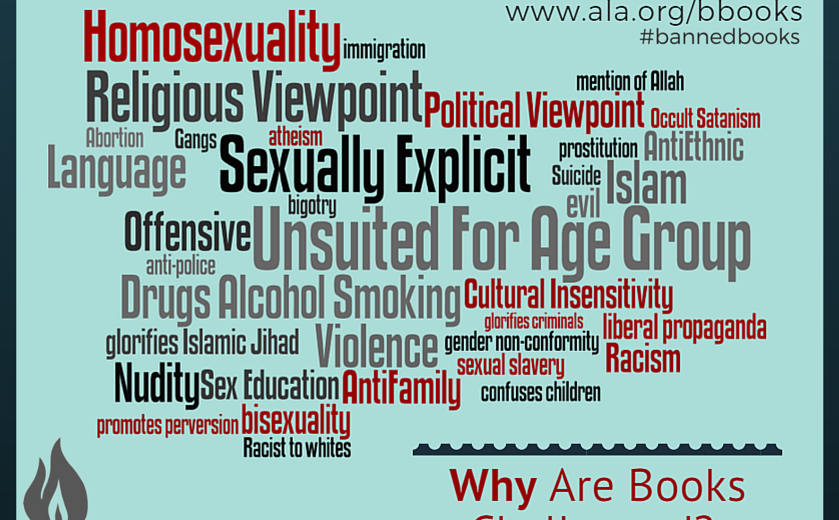

I hadn’t realized that Lysol to was linked to birth control during some of the other research I had done earlier this year concerning the Comstock Act and Margaret Sanger. The Lysol ads preyed on the public’s self-esteem by making them self-conscious enough to purchase their product, as most advertising is wont to do. But these ads have an even scarier undertone, the fears of women living at a time with no reliable or affordable birth control nor the means to educate themselves about what was available to them.

When I went to Lysol’s “Our History” page, I first noticed the tagline “Over a Century of Healthing.” Health? Is this a word? Apparently, it’s not a word but sort of a thing. Thanks to Google for providing me the first search hit that included a woman who referenced Lysol and Healthing. She was part of Lysol’s Healthing initiative and stated that it was, indeed, a word. A word invented for a health initiative is not really a word, especially since it’s not even in the dictionary. It was Lysol’s way of describing that you’re not just cleaning when you disinfect with Lysol, you’re healthing since you are decreasing germs and the spread of infection. But enough of the grammar rant, back to the history.

The Lysol’s history page only mentioned how it has helped families do more for health since 1889 such as ending a cholera epidemic, in 1918 was the first effective means of fighting the flu, and in 1930 was introduced to drug stores and hospitals. No mention of douching but I don’t blame them. Lysol is an effective germ-killing cleaner, one that I use in my own household, and would I imagine they would love to distance themselves from that dubious era in their advertising. Indeed, Lysol was introduced by Dr. Gustav Raupenstrauch to help end a cholera epidemic in Germany and used in 1918 to combat the Spanish Flu pandemic.

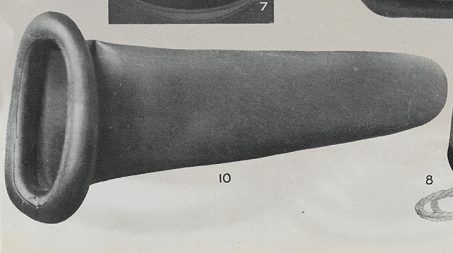

The product originated in Germany, migrated to Great Britain then landed in America. A combination of cresol and soap (most likely castor oil soap) made Lysol a powerful cleaner but also a toxic skin irritant that can cause blistering and burns. Despite this, starting in the 1920’s an extensive ad campaign was introduced suggesting diluted Lysol as an essential part of feminine hygiene.

Ads showed women with concerned expressions on their faces and copy that talked about the marital distress caused by lack of proper hygiene. Lysol cured everything from fatigue to foul odor, along with being the answer to your husband’s lack of interest and avoidance of intimacy. Why even the elegant women of Berlin used it! Lysol was the perfect antiseptic for marriage hygiene.

Yep, the ad actually says marriage hygiene.

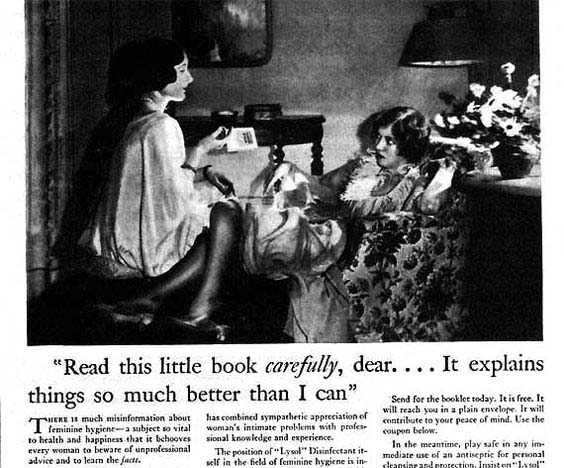

There was even a booklet available to teach you all about how to use Lysol since “There is so much misinformation about feminine hygiene.” The photo in the ad shows a proper Margaret Dumont-like mother offering the booklet to her attitudinal teen flapper daughter. Over the years the ads were geared towards women struggling with inattentive spouses. They beat on locked doors, were caught in spider webs, and drowning in doubt and misgivings. You could even take a love quiz, but it’s for married folk only. Apparently, women were, and other ad said, ignoring one small intimate physical neglect that could rob them of their husband’s love. Sadly, all these ads put the blame solely on the wife.

Couples therapy was pretty much out of the question during this period, so there was no way to find out if other issues such as depression, being trapped in a loveless marriage, or any other valid reasons for marital troubles were actually at fault. There could be another reason why there wasn’t enough intimacy in a relationship, the fear of getting pregnant. We were still in the midst of the Comstock Act that prevented any information or delivery of contraception to the public. According to historians such as Kristin Hall and Andrea Tone, these ads were also selling contraception. Douching post-coitus was a popular method of birth control. Since it was cheaper and easier to get than condoms or diaphragms, Lysol was the best-selling contraception method for 30 years.

Douching, in general, is bad for vaginal health, using a caustic disinfectant made it an even worse option. In 1952, the makers of Lysol exchanged the cresol for another chemical that made it less toxic, but it was still dangerous to use. Lawsuits were dismissed as allergies. It wasn’t even an effective method of birth control as a 1933 study showed that half the women who used it got pregnant. It wasn’t until the 1960’s and the advent of the pill that Lysol began to fade in popularity. It’s been so long most people had no idea the cleaner we use now (that recommends avoiding contact with eyes, skin, and clothing) was used this way.

And if you weren’t into Lysol, there was also Listerine. But that is another douche story for another time.